After more than 40 years of operation, DTVE is closing its doors and our website will no longer be updated daily. Thank you for all of your support.

Ovum: When Netflix runs out of steam

All good things come to an end. And so it will be with Netflix’s growth spurt. At some point, the pioneering online video provider will run out of new customers willing and able to subscribe – provided it sticks to its current business model. But what if Netflix were to pursue more radical options?

All good things come to an end. And so it will be with Netflix’s growth spurt. At some point, the pioneering online video provider will run out of new customers willing and able to subscribe – provided it sticks to its current business model. But what if Netflix were to pursue more radical options?

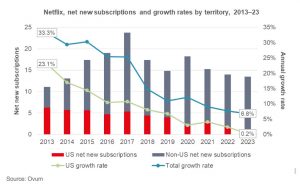

It’s first worth stressing that Netflix’s model – offering ad-free, subscription-based access at largely similar prices worldwide – has plenty of distance to run. Although the number of net new Netflix subscriptions peaked in 2017, Ovum forecasts that the company will still be adding over 13 million annually, even in five years’ time.

By then, however, its annual growth rates in many of the world’s largest markets will have slowed from double-digit to single-digit percentages. In the US, Netflix’s subscriber base will grow by just 0.2% in 2023 (see Figure 1). And despite its global expansion, the US will still be a hugely important market for the company, accounting for about a third of subscriptions and revenues.

So how else can Netflix grow, beyond simply raising its prices? Ovum has identified three options.

1. Make mobile video even more affordable

Ovum forecasts that over 500 million people in India will have smartphones and data connections powerful enough to watch online video in 2022, yet Netflix will have fewer than 5 million subscriptions by then. Why? It’s about affordability.

Netflix has taken several steps to make its service more accessible and affordable in emerging markets, such as streaming technologies that consume minimal amounts of data and enabling people without credit cards or bank accounts to charge their subscriptions via their mobile phone bills.

But the main sticking point is Netflix’s US$7.99 entry-level price point – great value for consumers in developed markets but too expensive for many in emerging markets, where disposable income levels are often several times lower. Last month, the company was revealed to have acknowledged this issue by trialing a $4 per month “mobile-only” plan in Malaysia for access on one phone or tablet at standard definition quality.

For hundreds of millions of consumers in emerging markets, roughly halving prices won’t be enough. Put simply, subscription services aren’t the no-brainer they are in developed countries. In Malaysia, 75% of mobile connections are pay-as-you-go. In India, 95% are. If Netflix really wants to move the needle in these massive markets, it will need to explore more radical pricing and bundles through closer partnerships with local mobile operators.

2. Bring a truly fresh take on TV advertising

To be 100% clear, adopting a Hulu-like model where viewing is interrupted by ads before or during TV shows and movies would be a bad move for Netflix. Using ads to offer a “free” version would risk cannibalising its paid subscriber base, while showing ads to paying customers would ruin the viewing experience.

Instead, Netflix could invest in evolving product placement, the practice of including brands within the content and storylines of TV shows and movies. Around three in four Netflix shows already feature at least one example of this covert form of advertising, according to specialist agency Branded Entertainment Network. Augmented reality-like technology could take the concept to the next level, digitally inserting different products into videos for different viewers, so say, one sees a Coke and another a Pepsi.

There’s already a precedent in another globalised form of media, sport, with broadcasters overlaying “virtual advertising” over banners at matches. Vendors such as Accenture and Ryff are working on bringing more advanced technology to movies and TV shows. To put this opportunity in perspective, various estimates suggest advertisers will spend over US$20 billion on product placement this year; subscription online video services will generate US$32 billion, according to Ovum’s forecasts.

3. Reinvient itself as a TV ‘re-intermediary’

Netflix once looked set to become a kind of “Spotify for TV” – before content providers realised that selling their most valuable content to a single, increasingly powerful intermediary was not such a good idea. Netflix has since invested heavily in exclusive and original content to become more like HBO’s TV brand, while HBO, Disney, and others have sought to become more like Netflix.

But few established media companies will come anywhere near their inspiration’s level of success. In 2023, Netflix will account for around one in three online video subscriptions worldwide (excluding China, one of the few places where the service is not available). In many countries, its market share will be well over 50%, leaving most rival apps fighting over relatively small numbers of subscribers.

Netflix could use its scale to help these providers to survive, by reinventing itself as an Amazon Channels-like aggregator handling marketing, technology, and customer support in exchange for a cut of fees from subscriptions it brokers or manages.

The question is whether another company will get there first – not least Amazon. The battle to become the platform that profits most from helping consumers navigate today’s fragmented TV landscape will be fought by the biggest names in media and tech, including AT&T Time Warner, Apple, Comcast Sky, Google, and Liberty Global. Netflix will be increasingly dependent on such “re-intermediaries” for attracting subscribers, billing, and driving viewing – unless it becomes one itself.

Playing safe versus changing the game

Never underestimate the power of one big idea – and one company’s ability to deliver on its promise. But no single idea has infinite potential. Sooner or later, Netflix will need to look beyond the limits of its current business model – just like when it made the truly game-changing move from DVD rentals to online streaming.

Straight Talk is a weekly briefing from the desk of the Ovum’s Chief Research Officer. To receive this newsletter by email, please contact us.