After more than 40 years of operation, DTVE is closing its doors and our website will no longer be updated daily. Thank you for all of your support.

The tangled web

The range of companies offering online TV services continues to grow, as do the types of services on offer. All are still finding their feet to some degree. But could the humble TV set prove to be the saviour of online video? Graham Pomphrey reports.

Major investments are being made in increasing the capacity of broadband networks, which combined with advances in streaming technology means that video is being broadcast over the internet at increasingly high quality, and some online TV services are having a profound impact on the way people watch TV.

In the UK the BBC’s iPlayer is establishing itself as a genuine mass-market online proposition, with an appeal far beyond the tech-savvy youth that the internet used to be associated with. The latest figures from the BBC continue to impress: in 2008, there were a total of 271 million requests to view programmes online, 41 million of which came in December alone.

The US equivalent of iPlayer, Hulu, celebrated its one-year anniversary in March and any fears that a joint-venture between two broadcasters (in this case NBC and Fox) would be doomed to failure have been allayed. A recent report in Newsweek magazine showed that Hulu managed to make a US$8.5m (?6.4m) gross profit last year, while video-sharing website YouTube generated no profit at all, despite attracting 10 times as many visitors each month. If this proves one thing, it’s that getting the business model right for online video can be tricky.

Internet to the TV

It also suggests that advertisers are wary of stepping outside the walled garden to advertise around content that can’t necessarily be trusted in terms of quality and subject matter. In contrast, Hulu and iPlayer’s managed services benefit from the breadth of quality, prime time programming at their disposal. At last month’s IPTV World Forum in London, the BBC’s programme director, IPTV Richard Halton, told delegates: “We’re in no doubt that while iPlayer is a fantastic service, it’s successful because of the content we’re able to offer.”

It also suggests that advertisers are wary of stepping outside the walled garden to advertise around content that can’t necessarily be trusted in terms of quality and subject matter. In contrast, Hulu and iPlayer’s managed services benefit from the breadth of quality, prime time programming at their disposal. At last month’s IPTV World Forum in London, the BBC’s programme director, IPTV Richard Halton, told delegates: “We’re in no doubt that while iPlayer is a fantastic service, it’s successful because of the content we’re able to offer.”

Despite the overwhelming success of iPlayer, like the online TV world at large, the BBC is not sitting still. Barely weeks after the UK’s Competition Commission put the brakes on Project Kangaroo, the online video joint venture between the BBC’s commercial arm and broadcasters ITV and Channel 4, the corporation revealed details of Project Canvas, a proposal to work with content owners, ISPs and consumer electronic device companies to develop a single standard to enable the rapid adoption of IP-connected TVs in the country.

The service would allow viewers to watch on-demand services, including iPlayer, and other internet content via the TV. One of the reasons the BBC is keen to forge ahead with the plans is the appetite the UK public is already showing for watching iPlayer on TV. It launched on Virgin Media’s cable platform last May and that outlet already represents over a quarter of all iPlayer views. Bearing mind that the Virgin Media service is only available to 3.5 million homes, it’s an impressive achievement and probably says a lot about consumers’ preferences for watching video on the TV rather than the PC. “iPlayer has been re-versioned for the Virgin Media television service and not surprisingly we’ve found audiences adopting IP delivered content to the TV set even more strongly than to the PC… What it said to us is that the progress of IP connectivity to the TV set is inevitable and that fantastic content is important,” Halton said, adding that catch-up TV services are only likely to be “part of the jigsaw”. IP connectivity could mean access to a whole range of web-based services from third parties.

The BBC has applied to its governing body, the BBC Trust, for permission to form a joint venture partnership to set and promote a common standard for delivering the service via a broadband-connected device such as a set-top box. It is the BBC’s intention that devices meeting the standard would enable the delivery of TV services, including HD channels, without a subscription fee, in a similar model to the UK’s Freeview DTT service, as well as over-the-top content.

By developing a single standard for IP connectivity, the BBC hopes to make the process of publishing content for over-the-top delivery to TV sets much easier for content owners. The iPlayer, for example, is available in 11 formats on devices as diverse as Nokia N96 mobile phones and Nintendo Wii games consoles. “As a content provider, we’re conscious of the need to try to continue investing in content rather than spending money on varying [existing] content to meet the needs of multiple devices,” Halton said. “We’d like to see a world emerging where there’s an approach to common standards that enables us to make content as widely available as possible without having to repurpose it for every screen.”

Online strategies

Of course, the BBC isn’t the only company to have launched an online TV service. Across Europe, broadcasters, operators and aggregators have launched their own variations, although few are blessed with being publicly funded in the same way as the BBC. Danish cable operator YouSee launched a web TV service last year, which consists of 17 aggregated channels for a monthly subscription fee of ?14 or ?5 per day. Users can also download over 450 movies from an on-demand catalogue. The company has two distinct business models for the service. By offering existing broadband customers access to a basic package of channels for free, YouSee hopes to increase the uptake of broadband subscriptions. The service also gives the company access to homes across whole country, not just the ones its cable network passes, thus opening up half of Danish homes to its pay-TV services. “It’s a good way to reach those homes that we don’t pass with cable and increase revenues at the same time,” Anders Blauenfeldt,

“Historically, online TV was a fairly niche experience but audience sizes are continuing to grow as broadband speeds are increasing.”

Tim Napoleon, Akamai

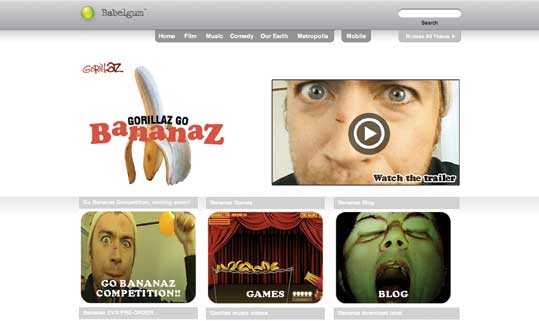

YouSee’s vice-president of product development told delegates at the IPTV World Forum. However, unlike the BBC’s iPlayer, and potentially Canvas, the company has no immediate plans to deliver the service to TV sets. “The quality is not as good as digital cable, but this is specifically for the PC. The TV experience should be via traditional cable infrastructure but we market this as a secondary offering – something in addition to a TV subscription,” said Blauenfeldt. The company has deployed set-top boxes that have the potential to support over-the-top content via the open internet, but Blauenfeldt said it has no plans to offer such a service, preferring instead to develop its own catch-up product for the TV. He also said the company wasn’t threatened by broadcasters offering their own online catch-up TV services, adding that consumers prefer to have one destination for all content: “There’s a golden opportunity to act as an aggregator and we’re in a well-placed position. People don’t want to use a number of different services to view content.” While YouSee is an example of a pay-TV operator launching online aggregated services, other companies have been offering similar services without the luxury of an established pay-TV service and the relationships with broadcasters that brings. One of them, Babelgum, offers high quality, long-form programmes and films from a range of broadcasters and producers, including the BBC, Reuters and sports company IMG.

Director of content Mark Cranwell says that far from feeling threatened by broadcasters’ online TV services, they provide “healthy competition”, although he admits to making “strong” submissions to the UK’s Competition Commission opposing Project Kangaroo, due to its alleged anti-competitiveness. “I think we will all jockey for our own position in the market, offering different but equally good services,” he says. Cranwell believes the advantage Babelgum has over broadcasters is that it is not tied to what a broadcaster has licensed for its TV service: “We aggregate around specific, focussed topics and provide a rich and varied experience for a consumer who has an interest in our offering.” The company is also keen on securing a mix of high-quality, mainstream programming and exclusive content, and has even commissioned some of its own programming. “It is question of where we can source the best content for our service. In one sense, it’s good that I can go to a large supplier of content like BBC Worldwide [the BBC’s commercial arm]. However, I would be just as happy, and we have done so, to go to individual producers on a case-by-case basis for content. The emphasis is on quality and interesting windows. That is why we have commissioned our own original content and taken some content exclusively, in order to offer something unique and compelling to the viewer rather than simply licensing existing content on a non-exclusive basis that is available widely on other platforms.”

Business models

However the internet is used to deliver video to consumers, the perennial question remains – where is the business model? Babelgum is ad-supported, although it benefits from being financially backed by Italian telco mogul Silvio Scaglia. UK-based online TV aggregator BlinkBox offers a mix of ad-supported free and paid-for premium content. The company has signed deals with major studios including Universal, Warner Bros and Paramount as well as broadcaster Discovery and several producers of various sizes. The company aims to combine the latest blockbuster releases and TV series, as well as library content, with social networking. Users can pay to download content to rent or to own, or they can watch a selection of free clips and send them to friends along with a message. The site also offers a selection of ad-supported free content.

The site was launched last April and has already established itself as one of the UK’s leading online video portals, notching up 581,000 unique visitors in January according to internet market research company Comscore, which is more than incumbent pay-TV operator BSkyB’s Sky Player service, MTV UK’s online portal and video aggregator Joost. Co-founder and CEO Michael Comish believes the key to monetising online video content is to offer a mix of good quality content, to be prepared to work with a range of business models from the start and to take advantage of the emotional ties people have with TV shows and movies. “We offer the ability to share the latest releases and to engage with others. The social element of the internet is very important. Think about the way kids watch TV whilst using Twitter or Facebook at the same time,” Comish said at the IPTV World Forum. “You need to start with a business model from day one, rather than months or years down the line.”

The site was launched last April and has already established itself as one of the UK’s leading online video portals, notching up 581,000 unique visitors in January according to internet market research company Comscore, which is more than incumbent pay-TV operator BSkyB’s Sky Player service, MTV UK’s online portal and video aggregator Joost. Co-founder and CEO Michael Comish believes the key to monetising online video content is to offer a mix of good quality content, to be prepared to work with a range of business models from the start and to take advantage of the emotional ties people have with TV shows and movies. “We offer the ability to share the latest releases and to engage with others. The social element of the internet is very important. Think about the way kids watch TV whilst using Twitter or Facebook at the same time,” Comish said at the IPTV World Forum. “You need to start with a business model from day one, rather than months or years down the line.”

Brightcove provides a publishing and distribution platform to enable third parties to deliver web-based video services. According to founder and CEO Jeremy Allaire, the business model of choice for monetising online video is ad-supported programming, although he believes there is much work to be done to optimise revenues. “We’re in the rudimentary stage of working out what kinds of advertising products work for consumer, producer and advertiser,” he says. “We’re still in the world of re-factoring short TV commercials for the web, which is fine because it does work, but there’s definitely a lot more potential. Online, you can engage with the user and conduct transactions. That hasn’t really happened yet, but it will create value going forward.”

Even before online services consider the technology choices for advanced advertising opportunities, they need to build up a critical mass of users. Something made all the more difficult by the fragmented nature of the internet and the seemingly infinite number of websites vying for eyeballs. “It you look at a commercial broadcaster, their traditional business has gone flat and online is growing so this is one area where they’re increasing investment but they must drive more users into their sites,” says Allaire, adding that syndicating content across multiple sites is vital.

“Content owners need to have a hub and spoke distribution strategy where their branded destination site is at the hub,” he says. On that site they can offer an immersive experience with the full range of their content and in that environment they can monetise it most effectively because they’re in complete control, he explains. “But people aren’t just going to go there. People will also visit YouTube, Bebo, MySpace, Yahoo, blogs etc. Online video syndication is about empowering the content owner to take their content and make it available on those other websites in a seamless way.” He says that syndicated content can be of high value to third-party websites by making them more attractive to users, which means they will stay there longer, keeping advertisers happy. “Content owners want to make sure they sell the advertising around that content and that they can get data back to help them understand what type of content is doing well,” says Allaire.

One of the problems faced by advertisers looking at the online space has been that of having to develop various derivatives of their creative to work across different websites in order to get the scale to make a campaign worthwhile. This overhead has taken money away from media buyers and impacted the overall value of advertising, according to web services provider Akamai’s chief strategist, media, Tim Napoleon. He explains that his company has been working with broadcasters to develop standards for in-stream advertising in an attempt to overcome the problem. “We’ve been working with standards bodies and broadcasters to create standards around things like how the ads are sequenced, how they’re tracked to the ad server and how they play back in video players,” he says.

Improving the web

Napoleon says one of the reasons for the growth in popularity of web-based services including Hulu and iPlayer is down to the fact that ISPs and consumers continue to upgrade to faster internet speeds, which means the experience is moving closer to broadcast quality. Akamai produces a quarterly State of the Internet report, the latest of which shows that in every western European country, over half of the population received broadband speeds of at least 2Mbps. Faster broadband speeds, coupled with improved video technology has improved the quality of experience for consumers, Napoleon says: “Historically, online TV was a fairly niche experience but audience sizes are continuing to grow. Throughout Europe, broadband speeds are increasing. At the same time, companies have begun to implement codecs used in traditional digital broadcast offerings, such as H.264 that were only available in proprietary set-top boxes but are now available in fully distributable desk-top clients.”

[icitspot id=”10384″ template=”box-story”]

Akamai plays a key role in optimising the internet’s performance via a number of globally distributed servers. The growing popularity of online video is naturally putting a strain on the internet, particularly as the length and quality of videos available have increased over time. But what kind of impact will a mass-market over-the-top service delivered to TVs such as Canvas have? Cisco’s chief technology officer Europe and APAC, service provider video technology group, Nick Fielibert, says the implications are clear. “For OTT services, as long as it’s a small service with only a few people using it at any one time, the internet will work well. But if lots of people are using it, the internet simply won’t be able to cope. If every BT customer streamed HD content at the same time, there could be a big problem.” Last year, the company unveiled Medianet, it’s latest strategy for dealing with the IP delivery of video and rich media after predicting that nearly 90% of all consumer IP traffic will be from video in 2012, and that global IP traffic will reach 44 exabytes per month by 2012, more than six times the total traffic in 2007. Medianet brings together a number of existing components to offer an end-to-end architecture for IP networks. “You have to be able to scale the network more efficiently, says Fielibert. “You have to manage the unicast content more efficiently, which means optimising the network by caching the appropriate streams and by distributing servers properly.” Which, of course, costs money. But who will take the strain? In the case of Canvas, it’s unlikely to be the BBC. According to Fielibert, an ISP might offset the cost of improving its network by charging customers more for a premium service designed specifically for consuming OTT content. How this would play out with consumers that are being promised a free-to-air proposition remains to be seen.

There’s no doubting that online TV is making inroads in terms of developing into a mass-market proposition. It might seem ironic that content could move from the TV screen to the PC and back to the TV via an IP-connected round-trip, but consumers are showing a clear appetite for the convenience offered by online services and all parties are looking at ways to benefit from that.