After more than 40 years of operation, DTVE is closing its doors and our website will no longer be updated daily. Thank you for all of your support.

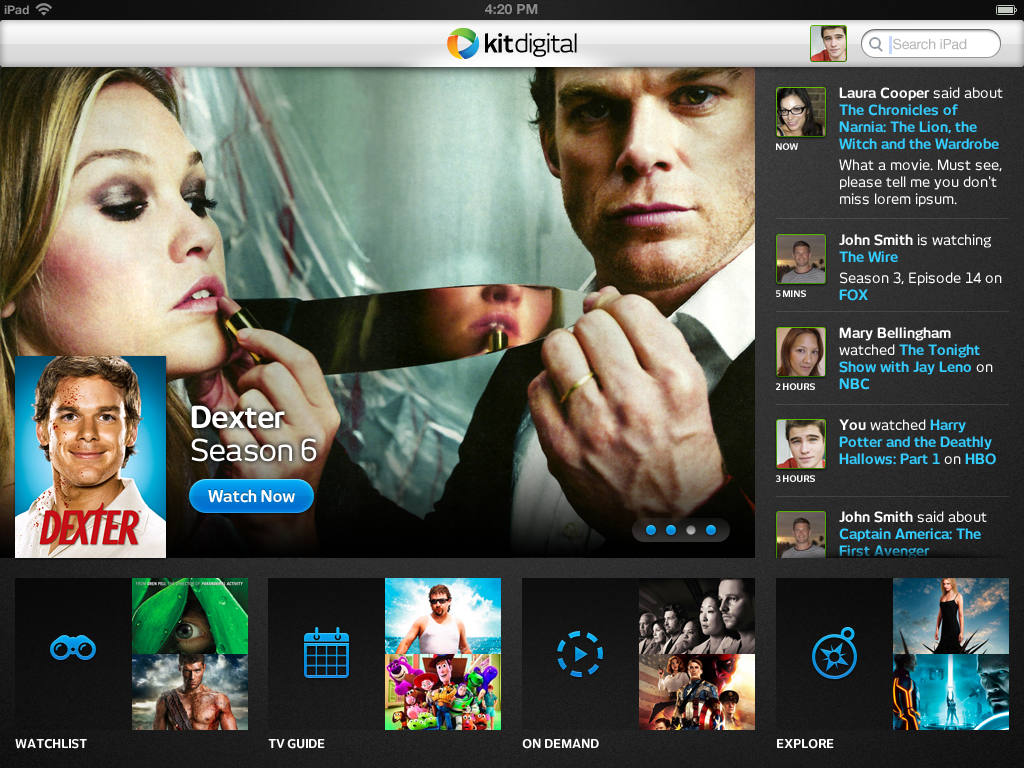

Good companions: the rise of second screen interaction

Use of ‘companion screens’ in the form of tablets to smartphones to deliver interactivity is a hot topic just now. But there are still many issues to iron out. Stuart Thomson reports.

Use of ‘companion screens’ in the form of tablets to smartphones to deliver interactivity is a hot topic just now. But there are still many issues to iron out. Stuart Thomson reports.

The use of ‘companion screens’ is one of the topics currently dominating debate at the new media end of the TV business and technology conference circuit. This is essentially the revisiting of something that was widely discussed during the first wave of interactive TV development over a decade ago – namely, the use of a second screen to interact with what was happening on the main TV screen rather than interacting with the TV itself via a remote or a wireless keyboard. Observers at the time identified the simultaneous use of a laptop and TV viewing as something of a growing phenomenon in the US, though less so in Europe, where pay TV companies led the way in developing interactive applications on the TV itself. Now, with the development of the iPad and the smartphone, the idea that ‘interacting’ with the TV can be displaced to another device has returned with a vengeance.

Recent Nielsen surveys in the US market showed that 87% of individuals with a tablet used that device at least once a month while watching the TV, while 88% of those with smartphones did so. Some 42% of tablet owners and 40% of smartphone owners used their devices in front of the TV on a daily basis.

Of those that used these devices while watching the TV, 42% accessed social networking sites (with no distinction made between during programmes and commercial breaks), while 30% checked sports scores. Some 29% used their devices to look up information related to a show and 19% looked up products shown on adverts. Some 13% looked up coupons or deals related to an ad.

Enthusiasm

In the UK, broadcasters have taken to developing companion screen applications with enthusiasm. The BBC, for example, plans to launch its first app associated with its Antiques Roadshow show in September. The BBC will introduce an app for smartphones, tablets and PCs that allows viewers to guess the value of collectables brought by members of the public on the show. There will also be a red button version of the app available. Victoria Jaye, head of IPTV and TV online content at the BBC, has said that over the next 18 months the BBC will focus on developing a handful of pilot versions of synchronous companion screen apps that would build on audience needs related to programmes as they are being watched, using its experience with red button services as a guide. The broadcaster has already piloted apps around its Frozen Planet and Secret Fortune series on BBC1.

However, Jaye cautioned that the companion screen market was still at a very early stage of development. One of the main challenges is scale, she said. To enable apps to work, “we need to get numbers of people onto these platforms”, said Jaye.

UK commercial broadcaster ITV and production giant FremantleMedia meanwhile recently launched companion screen voting for the Britain’s Got Talent show, using technology from Mobile Interactive Group and app developer Tellybug, enabling viewers to vote via their iPhone, iPad and iPod Touch directly from the Britain’s Got Talent app, which received over 500,000 downloads across the series and saw peak traffic of up to 130,000 users per episode. ITV also recently broadcast its first adverts enabled by Shazam, this time during the final of the Britain’s Got Talent, on May 12.

Orange meanwhile recently launched its TVcheck app in the UK. The social TV application, which allows users to access games and chant about shows with friends, is available from the UK Apple App Store for iPhones, and works works with 25 free-to-air channels in the UK, including the BBC, ITV, Channel 4 and Channel 5.

Elsewhere in the schedules, Fox’s FX channel recently ran a companion app for its Walking Dead show, developed for the channel by UK technology provider Red Bee as part of its Red Discover product set. The app included a playalong game that allowed viewers of the show to predict how many zombies would be killed in the course of the episode, who would do most of the killing and which weapons would be used, with points awarded for each that could then be compared with others.

Fox had recorded 63,600 downloads of the app by the end of April, with just over 345,000 separate game plays. The broadcaster estimated that about 20% of viewers equipped with the necessary iOS devices had downloaded the application.

Participation element

A number of pay TV operators have also experimented with second screen interactivity. Most have to date focused on TV everywhere delivery – allowing subscribers to view channels, or a subset of channels, on mobile devices, but some have experimented with making social TV features available on second-screen devices, or allowing the use of second screens to access more detailed user guides and as a remote control.

While pay TV operators have focused on taking user guides to second screens, the development of apps that allow users to interact with specific programmes has been the province of broadcasters and production companies. The majority of companion screen apps developed to date have been around shows with an obvious participation element – such as quiz or talent shows – rather than scripted drama. In this case FX’s main aim was to create a buzz around the show and the channel originally looked at creating a Facebook app before contracting Red Bee to develop something for the iOS platform.

For Steve Plunkett, technology and innovation director at Red Bee, companion screen apps can work for broadcasters if they meet the needs of both content creator and user. For the broadcaster’s marketing department it can create a buzz around a particular show, and can also provide insight into who watches it and when; for the fans of the show it enriches their experience.

Using companion screen activity to measure and monitor use of media on the main screen offers myriad opportunities for broadcasters and content creators to find out in much more detail than before how, when and where people are actually viewing the show, including where they fast-forward and rewind through it. “If people are time-shifting viewing and watching shows the next evening you can measure that through the use of the second-screen app. You can start to see what the viwing pattern for the show is,” says Plunkett.

[icitspot id=”25356″ ]For Plunkett, there are three broad types of companion screen app. At a basic level, there is the most widely deployed type of app – a generic EPG-type app not specifically branded around a particular show title that provides contextual information about a range of programmes. At a slightly more sophisticated level, there are apps that are branded around particular shows and include games, for example, related to that show. Finally there are apps that could influence what’s actually happening on the main screen – this could mean everything from comments made by viewers being integrated with onscreen graphics to, potentially, the audience actually directing the outcome of the show itself, possibly via multiple endings personalised for particular groups of viewers and so on.

Plunkett believes that the ‘sweet spot’ for companion apps is currently in the middle group – apps dedicated to particular shows, many based on the all-consuming idea of ‘gamification’ – building games around the TV viewing experience to further engage viewers. Other applications of companion screens could include asking viewers to react to or comment on news programmes.

Different approach

Taking a somewhat different approach to companion screen activity, Zeebox, the UK-based company founded by former YouView technology chief and iPlayer creator Anthony Rose, has sought to create a consumer proposition offering clear functionality that can work across different ecosystems and different TV shows. For Rose it makes little sense for content providers to build native apps for specific shows as the appeal of the any one app will be too limited to make it worth the effort. “It’s not going to scale if every time you change channel you need to download a new app,” he says.

Having assessed the market requirements, Rose concluded that the most viable approach would be for Zeebox to develop a consumer proposition with a consumer-facing brand.

Rose believes that broadcasters have, for the most part, yet to identify what they want to do in this space, with different departments often pulling in different directions. Strategy departments want to work out where the advertising market is going and what will happen in three to five years’ time, new media teams want to build apps themselves, and programme makers have a budget for social media marketing that they want to use to drive viewers to their content. Uniting these groups around a single point of focus is challenging enough. It then makes little sense to develop an app and put it through – say – Apple’s approval process (and a similar process for other ecosystems) when it is likely only to be used for one show or series and then never used again.

As far as consumers are concerned, Rose believes they are primarily interested in being given recommendations about what to watch and, secondarily, being presented with additional information around shows they are currently watching, such as information about products, recipes, and background information about people who appear on programmes. The latter also applies to recorded and on-demand content as much as linear scheduled programmes, meaning that some form of content recognition could be necessary. “Finding something to watch is predominantly about live TV, while finding information should work with recorded content,” says Rose. In the case of the latter, pay TV providers could stand to benefit from playing a more significant role in developing companion screen apps. “We know that Sky and Virgin Media users watch a lot of VOD and catch-up TV and we would like Zeebox to work with that,” he says.

However, says Rose, social applications today are mostly concerned with enhancing live TV shows with mass followings, such as big primetime talent shows.

For broadcasters and content producers, meanwhile the aim is to extend their relationship with audiences beyond the airing of the actual programme itself and, secondarily, to collect information about viewing patterns that can be analysed and put to use, for example by advertisers.

On advertising, Rose is enthusiastic about the range of uses to which second screen applications could be put, delivering not only viewer analytics but advertising – related functionality in the form of synchronised transactions, enabling advertisers to prompt users of iPads to buy goods or seek out additional promo material.

The use of second screens in this way may do broadcasters no favours if they are cut out of the picture. However, in the case of Zeebox, BSkyB, which is an investor in the company, has exclusive rights to advertise in Zeebox’s application, enabling it to sell second screen advertising around shows on its own proprietary channels.

Civolution, a watermarking specialist that has delivered technology to synchronise second-screen apps and provides content monitoring services, by combining its knowledge of what’s being aired with knowledge of what people are watching through its synchronisation technology, is an example of a company that can create an advertising platform that could allow brands to book ads on second-screen devices according to what is playing on the main screen.

“You can target the ads because you know the profile of the second screen user,” says CEO Alex Terpstra. “You can also market the brand interactively on the tablet.”

Fragmentation

While broadcasters are clearly looking at companion screen activity with a great deal of interest, the fragmented nature of a space that is still very much in its infancy means that the benefits to them are as yet unproven.

“With synchronised communication the audience can be quite small because they have to have the same given app for the companion activity open and have to be watching live,” says Mark Hyland, vice-president, sales and marketing at US technology provider QuickPlay, which provides delivery of multiscreen video for pay TV service providers in the US. For this reason, he says, development of companion screen apps has so far been limited largely to big primetime shows.

QuickPlay has worked with US telco Verizon on companion activity around the Indy Racing League, which Verizon sponsors. Verizon doesn’t have rights to mobile video coverage of the IndyCar races – the broadcast rights are held by ABC – but the company has taken advantage of rights it does hold through its sponsorship deal to deliver ancillary information and statistics around the races, including news, video-on-demand and still photos. “It’s a true companion experience in that it’s designed to be complementary,” says Hyland. “Because it’s all happening live it’s being streamed as close as possible to the live event.”

The service is delivered in the form of a native app for the Android platform and an HTML5 app for iOS devices. There is, however, no need for content recognition and synchronisation with the broadcast coverage of the races. For now QuickPlay is focusing primarily on the delivery of video services to multiple devices, which it sees as a greater priority for pay TV providers.

Also keen to target multiscreen consumption of video, of course, is a growing range of providers that includes the likes of Netflix and Lovefilm in the UK. In the US, one of the latest entrants is Technicolor, which plans to launch its own over-the-top multiscreen service M:GO this summer. Technicolor will offer electronic sell-through and transactional video-on-demand to M:GO users via a range of devices. According to chief operating officer Greg Gudorf, while Technicolor is looking to develop M:GO as a consumer brand it is also open to partnerships with other pay TV providers. The company is looking to tie up with service providers in the US and – potentially – internationally to provide them with a multiscreen content offering and user experience. Gudorf says that M-GO could also be deployed as a companion screen offering enabling service providers to deliver access to its own and third-party content via user interfaces on tablets and other devices. “Operators with legacy equipment are looking to experiment in embracing multicsreen to hold onto their customers,” he says. Gudorf says there are “several different paths” by which M-GO and operators could work in partnership. One was to act as a replacement technology for legacy user interfaces, while another was to help pay TV providers unable to swap out existing set-top boxes to reach new screens. Another was for existing pay TV providers to outsource all or part of their VOD offering to M-GO, he says.

While the companion screen app space remains fragmented – clearly a problem if broadcasters and developers are to build apps that can scale to millions of users across multiple device types – Zeebox’s Rose sees little prospect that SMPTE-type industry standards will emerge to enable developers to achieve scale more easily. The industry will continue, he believes to be led by the most innovative firms, creating de facto standardised ways of doing things that others will follow. In part for this reason, the majority of broadcasters are likely to shy away from too much sophistication and from investing too much time and money in apps based around specific shows that are likely to have a short shelf life.

The main challenge is to put in place a back end infrastructure that can push and collect information to and from millions of viewers simultaneously. For Red Bee’s Plunkett the immaturity of the market for companion apps means that it is difficult to know exactly how robust systems need to be. “There’s the question of how do you cope with unexpected peaks in interaction,” says Plunkett. “Without further experimentation we could be in danger of overengineering because you don’t know how many people you will get interacting – you need to be able to cope with the maximum peak but how do you predict that?”

Using cloud-based infrastructure providers to deliver services could help mitigate the risk of building your own infrastructure. However, it is important to be able to react quickly and deliver new features at short notice.

Once the back-end infrastructure challenge has been solved, content provider must also be able to version their apps for different devices. While Apple’s iOS is a closed ecosystem with few variable elements, the Android system is much more complex, with numerous variations in implementation and a wide variety of devices with different screen sizes. The latter will have an impact on where app developers can place interactive ‘buttons’ on the screen, for example. And with other devices such as PCs, there can be problems around content recognition and synchronisation in the absence of microphones and so on. For some types of interactivity it may be simpler for content providers to create a web-based experience rather than a dedicated app. “If you don’t want to use audio you could create a web-based experience that looks like it’s designed for the iPhone,” says Plunkett. “But if you want to access the mic and so on you need to develop a native app. You could have a web application across all devices that’s attractive but you would lose out on some of the local features of particular devices.”

Companion screen activity requiring advanced features such as automatic content recognition and synchronisation of interactive features and prompts with what is happening on the main screen (see sidebar) is likely to remain a minority interest. Most work has been based around primetime shows that are assumed to be watched live rather than recorded or viewed on-demand. Plunkett says synchronisation for live shows can relatively easily be handled at the back end without the need for automatic content recognition. In any case, he says, broadcasters will want to avoid creating interactivity that is too specific to a particular episode of a show, requiring users to continually update their apps. “We have focused on a platform approach rather than standalone apps,” he says.

The cost of developing specific native apps for shows for each device ecosystem has led some to question whether developing a purely web-based app that can be viewed on all devices wouldn’t be the best way to go.

Between the use of native apps and web-based interactivity on second screens, however, Zeebox’s Rose believes there is a middle way whereby a native app is a ‘container’ for information from the web, with the advantage that the app will be promoted and sought by viewers within app stores. Apps should not be seen as ‘islands’ but should link to the wider social world through Facebook and Twitter.

A degree of openness would seem to be the key to a successful development of this market in a wider sense. The extent to which pay TV operators will be able to capitalise on the growing popularity of tablets and smartphones to extend ‘engagement’ with subscribers may depend on their willingness to open up interactivity on their own platforms, enabling app developers focusing on specific shows to link to the tablet version of the EPG for example.

However, there are dangers to operators too, as the use of new devices to interact with the TV offers opportunities for a wider range of industry participants – from advertisers and TV guide publishers to channel providers, production companies and web companies including the social networks themselves – to pull viewers away from the main screen and the operator environment towards a proliferating range of sources from which he or she can search for, discover, and interact with, TV programmes.