On-demand Africa

OTT TV providers are optimistic about the future of streaming services across the continent, driven by high mobile penetration. However, a number of obstacles stand in the way of progress. Andy Fry reports.

OTT TV providers are optimistic about the future of streaming services across the continent, driven by high mobile penetration. However, a number of obstacles stand in the way of progress. Andy Fry reports.

With a population of over one billion and forecasts of further growth, it’s no surprise that OTT players and analysts regard sub-Saharan African as a region with massive potential. However, the reality is that there are several key challenges preventing the region from achieving the rapid uptake seen in markets like China and India.

Recent research from IHS Markit neatly encapsulates the situation. On the one hand, says IHS, the economic indicators are good for both pay TV and OTT, with consumer spending on goods and services increasing by 20.3% between 2010-2017. But on the other, there are a series of roadblocks to growth. Putting the current size of the subscription-based OTT market at around one million, principal research analyst Constantinos Papavassilopoulos and research analyst Max Signorelli, who cover the region between them, say: “Online video has had a sluggish start compared to the rest of the world, and its impact continues to be minimal despite several service launches and expansions in recent years. Factors limiting both PayTV and online video include a lack of infrastructure, relatively high access costs, volatile exchange rates, a diversity of audiences in terms of language and stringent regulations in many of the key territories.” To that list could be added content piracy, which is prevalent across the region.

Drilling down into some of these points more deeply, it seems clear that the low penetration of cable and fixed line broadband across the region has limited OTT’s opportunity for expansion. It’s for this reason that Digital TV Research principal analyst Simon Murray expects mobile to be “the overriding factor” in the take up of OTT. With fixed broadband homes only expected to reach 13 million by 2022 compared to an estimated 486 million smartphones users, Murray says: “It is very important to stress the power that mobile operators have over the future of Sub-Saharan African OTT TV and video.”

Murray forecasts that mobile will help drive the SVOD market to 10 million customers by 2023, with six players accounting for 90% of that total. “The mobile operators know that they are in a powerful position,” he says. “Not only can they give OTT players access to their subscriber pools, but they can also conduct the billing, thus foregoing the need for SVOD platforms to insist on credit card payments.”

Whether this figure proves accurate will depend on mobile data charges, says Murray. Papavassilopoulos agrees: “The high cost of mobile data is a limitation on the widespread uptake of video content. The reason Indian OTT has grown so quickly is that Reliance came into the market and slashed data costs by as much as 75%. There is no obvious equivalent in Sub Saharan Africa.”

This is also the conclusion of Singapore-based Delta Partners. In a January 2018 analysis of the market, authors Pranav Modi and Eric Archer calculated that, “at current pricing levels of US$2/GB, even if one were to consume two hours of video per day in ‘low’ quality, the monthly mobile bill could rack up close to $36/ month. This, in sub-US$5 mobile ARPU markets, will undoubtedly be cost prohibitive. Telcos thus hold the key if OTT viewership is to gain critical mass – either through significant cuts in mobile data pricing, the launch of affordable unlimited bundles, or zero-rating partnerships with OTT providers.”

Likewise, both IHS and Digital TV Research identify Africa’s regional diversity as an issue when building a pan-regional OTT service. With around 40 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Signorelli says it is difficult for players in the market to create enough volume of quality local content to satisfy them all. As in Latin America, some content travels across the region but not enough to fully satisfy a subscription audience.

Modi and Archer make a similar point in their analysis: “Local content can account for over 90% of viewership for the mass market segments,” they say. “While global blockbusters are still critical to tap into the premium base, such content alone cannot be the recipe for success for any player operating in Africa. As such, pay TV operators and most OTT players are including local in their portfolios.”

For all of the reasons above, most of the OTT sector’s attention to date has focused on three major English-speaking countries: South Africa, Nigeria and Kenya. Each of these is an important market in its own right but also has the potential to act as a gateway into southern, western and eastern Africa respectively (for observations on French and Portuguese-speaking Africa see sidebar). As for the major OTT players, the picture tends to resemble what has been seen elsewhere in the world – namely a combination of well-established local media companies – typically pay TV providers – and global competitors.

Showmax

Currently, for example, one of the OTT frontrunners is South Africa-based MultiChoice, via its three-year old SVOD service Showmax. MultiChoice’s position in OTT has been built on its long-term strength as a pay TV provider. Active for 30 years, the company controls around 90% of its domestic pay TV market through digital platform DStv and is one of the few media companies to have gained traction across the region. At last count, it had around 6.6 million pay TV customers in South Africa and a further 6.9 million across the rest of the region.

Showmax launched in South Africa in 2015 and rolled out internationally in 2016. While there are no exact figures, it is reckoned to have around 300,000-400,000 customers in South Africa – a welcome boost when DStv is shedding premium subscribers. In overall terms, DStv is growing, but the last financial year saw it lose around 100,000 customers from the top subscription tier.

While MultiChoice is still intent on expanding Showmax’s pan-African footprint, it has also been preoccupied with how to protect its domestic pay TV/SVOD business from telco-operated services, such as Cell C Black and Vodacom VideoPlay, as well as the recent arrival of Netflix. Without focusing too much attention on the market, Netflix has picked up a similar number of subscribers to Showmax since it launched there two years ago. With Netflix recently switching from US dollars to local currency payments, it has, in effect, just become cheaper for South Africans and is expected to receive a boost as a result.

With this in mind, MultiChoice recently offered Showmax free to existing premium DSTv subscribers. It has just brought together Showmax Africa and DStv’s on-demand platform, DStv Now, into a single unit called Connected Video. The executive in charge of the new division is Niclas Ekdahl, who says the rationale for the unit is to “house all our OTT knowledge and experience in one place.”

Ekdahl’s assessment of the overall OTT opportunity pretty much echoes that of the research analysts: “It’s an exciting time to be in OTT in Africa,” he says. “DStv Now and Showmax both generate millions of play events weekly, so it’s fair to say that we’re well underway. Having said that, it’s still relatively early. South Africa is furthest along the adoption curve, with growing interest from other major markets like Nigeria and Kenya.”

Ekdahl says it is difficult to generalise about Africa as a whole “because customer needs and content preferences vary pretty widely”. But he agrees that the “data challenge” will determine the speed of uptake. “The majority of data connectivity across Africa is mobile-based, and the cost of that mobile data is in many cases still prohibitive. We see this improving over time, as FTTH and other solutions like fixed LTE become more prevalent, and we also see the telcos coming to the party with more affordable mobile data bundles. Continued movement on this is the key to mass OTT adoption in Africa.”

With regard to Netflix, he says: “DStv Now is a TV Everywhere service with news, live sport, linear channels and VOD, and it’s not available as a stand-alone service so it plays in a different space. Showmax, as an SVOD service, is in theory a competitor but we don’t see this as a binary either/or decision for customers. In fact, our experience has been that customers happily sign up for more than one service as long as each service gives them something unique.” Central to this uniqueness is an emphasis on local content. “We’ve got a mix of local content from the likes of Mzansi Magic and kykNET and we’re building on the success of our first Showmax Original, Tali’s Wedding Diary (right), with more originals in the pipeline”. In addition, he adds, there is international content from the likes of HBO,” says Ekdahl.

With regard to Netflix, he says: “DStv Now is a TV Everywhere service with news, live sport, linear channels and VOD, and it’s not available as a stand-alone service so it plays in a different space. Showmax, as an SVOD service, is in theory a competitor but we don’t see this as a binary either/or decision for customers. In fact, our experience has been that customers happily sign up for more than one service as long as each service gives them something unique.” Central to this uniqueness is an emphasis on local content. “We’ve got a mix of local content from the likes of Mzansi Magic and kykNET and we’re building on the success of our first Showmax Original, Tali’s Wedding Diary (right), with more originals in the pipeline”. In addition, he adds, there is international content from the likes of HBO,” says Ekdahl.

He also echoes Murray’s point about the complexity of taking payments from customers, “with credit cards more the exception than the norm. This is where partnering with others who have an extensive cash payments infrastructure in place makes sense. The telcos are examples of this, which is why we have add-to-bill arrangements with so many of them. In South Africa we also introduced retail vouchers, and in Kenya had an M-PESA payment option in place from launch.”

Netflix, Iflix and Kwesé

Netflix has relied primarily on international content to drive growth in South Africa, recent additions including Designated Survivor, Riverdale, Lost In Space, Altered Carbon and Trevor Noah’s Afraid Of the Dark (right). The company is yet to give any indication of its plans for African content, though local commentators were excited by this summer’s news that it was looking for a content acquisitions executive to focus on the Middle East, Turkey and Africa. That job went to Nuha Mohieddin Eltayen, a former CBC Egypt exec who started her new role in October. Given her expertise in Arabic TV, it’s too early to tell how much she will focus on sub-Saharan Africa.

Netflix has relied primarily on international content to drive growth in South Africa, recent additions including Designated Survivor, Riverdale, Lost In Space, Altered Carbon and Trevor Noah’s Afraid Of the Dark (right). The company is yet to give any indication of its plans for African content, though local commentators were excited by this summer’s news that it was looking for a content acquisitions executive to focus on the Middle East, Turkey and Africa. That job went to Nuha Mohieddin Eltayen, a former CBC Egypt exec who started her new role in October. Given her expertise in Arabic TV, it’s too early to tell how much she will focus on sub-Saharan Africa.

Parks Associates senior director of research Brett Sappington takes the view that Netflix “would love to establish a foothold everywhere, but they have finite resources in a very large world. They have to balance the value of the opportunity with the cost of marketing locally – and that means focusing budget where they can compete. That is probably why they established a marketing partnership with Kwesé in 2017.”

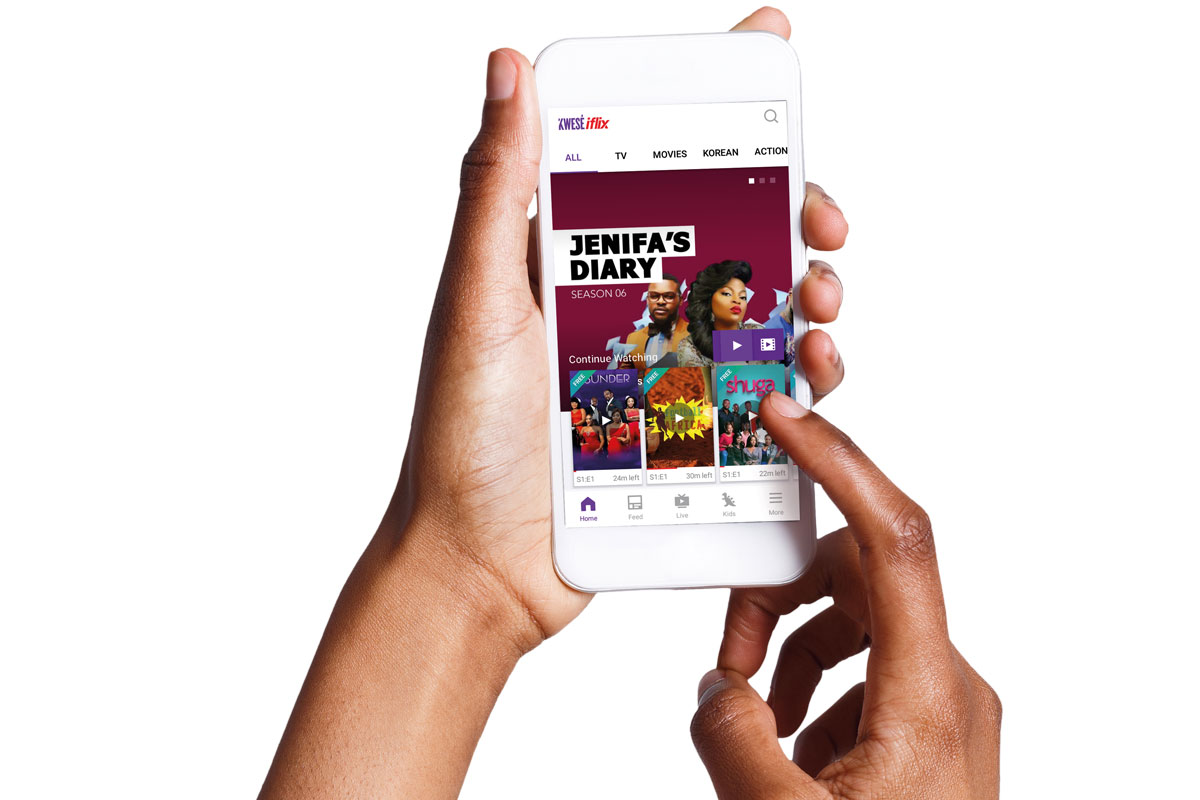

Another frontrunner in the expansions of African OTT, Kwesé is a pan-regional broadcaster that is part of telco group Econet Media, owned by Zimbabwe tycoon Strive Masiyiwa and headquartered in South Africa. The company made its way into the African media scene through the acquisition of premium sports rights such as NBA, NFL and the World Cup. Outside sport, it formed its alliance with Netflix in 2017, offering the service to customers via Kwesé Play. This year, it unveiled a new partnership with international VOD platform Iflix, called Kwesé Iflix.

Explaining the Kwesé Iflix link-up, CEO Mayur Patel says it offers a mix of international, regional and local content “curated” for an African audience – including live sport from Kwese, African-originated free-to-air channels and content acquired by Iflix for the region. “We have a free tier which offers an array for content – including a live English Premier League game at weekends. This acts as a way of introducing people to our VIP service, which includes the full content offer,” he says. Worth noting is that the VIP tier is available via a one-day, three-day, seven-day or 30-day pass. This is a reflection of the local industry’s desire to make access to subscription content as flexible as possible.

Although the service is available across all platforms – desktop, Roku etc. – Patel confirms that mobile is the major form of distribution in the region. While he acknowledges that the cost of mobile data is a barrier to entry, he says the situation is changing for the better: “Prices are decreasing and we are forming a growing number of partnerships with telcos that offer discounted video data as part of broader bundles. So while the market is nascent compared to other parts of the world, we’re excited by the growth in consumption.”

Regarding the Kwesé Iflix alliance, he says it is “a complementary collaboration that allows us to take the business to the next level. Iflix has a world class technology platform and great experience in content deals. Kwesé has a great suite of sports rights and broad reach as a result of its activities across broadcasting and telecoms. To succeed in this market you need great content, distribution and technology.”

Although Patel is based in South Africa, it is interesting to note that the Kwesé Iflix platform (pictured, top) has so far elected not to compete in that market, a decision that is probably explained by the high cost of going up against Showmax, Netflix and the local telcos. “Our primary focus is West Africa, centred on English-speaking countries like Nigeria and Ghana; and East Africa, especially markets like Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. In Southern Africa, our focus is more on Zimbabwe.”

Priorities going forward, he says, include improving the user journey and more emphasis on local content. The platform has made progress in providing mobile payment alternatives to credit cards and is also investing in scripted content from within East Africa.

MTN and StarTimes

Outside Showmax, Netflix, Kwesé, Iflix and iROKO, the companies most often referred to in relation to African OTT are Amazon, telcos MTN and Wananchi, and StarTimes, a Chinese-backed outfit that delivers affordable pay TV across DTH and DTT.

As with Netflix, South Africa is the focal point of Amazon’s attention. The company launched Amazon Prime Video there last year as part of its global rollout programme. Digital TV Research’s Murray puts Amazon’s current subscriber base at less than 100,000, but expects it to have 725,000 subs by 2023. The platform has ramped up the amount of content available in South Africa to 4,000 titles, from less than 1,000 last year.

The analysts at IHS stress that South African-based telco MTN will also have a part to play in the emerging OTT landscape. While the company has faced a series of setbacks in Nigeria, it currently has 240 million subscribers across the continent, making it a potential force in the OTT/SVOD landscape, says Signorelli. Expansion into digital music, financial services and e-commerce are all indicators that it sees data-based products as a strategic priority.

Linking back to Patel’s comments, this point was underlined by a September 2018 alliance between Kwesé Iflix and MTN Ghana, which makes the streaming service available using MTN Video Bundles. Commenting on the partnership, Noel Kojo-Ganson, acting chief marketing officer of MTN, said: “With the launch of the Kwesé Iflix app we are providing access to yet another avenue of digital entertainment. Video content is the future of mobile and our partnership with Kwesé Iflix will enable us to deliver some of the best international and local sports and entertainment to our customers.”

StarTimes is potentially a major driver of OTT, having built up a subscriber base of around 20 million pay TV customers across 30 Sub-Saharan African countries, largely by offering a low-cost alternative to DStv. A big part of StarTimes’ success has involved dubbing Asian series (mainly Chinese) into English, French, Swahili and Hausa, examples including The Beautiful Daughter-in-Law Era, The Ordinary World and Wildflower (left, from ABS CBN in the Philippines). Increasingly, it has also unveiled significant content investments and alliances from outside Asia. On the sports front, for example, it acquired exclusive live rights for UEFA Europa League in sub-Saharan Africa until 2021 (excluding South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland). It also signed deals with Discovery and Fox to air several channels via TV and OTT, including a new female lifestyle channel.

StarTimes is potentially a major driver of OTT, having built up a subscriber base of around 20 million pay TV customers across 30 Sub-Saharan African countries, largely by offering a low-cost alternative to DStv. A big part of StarTimes’ success has involved dubbing Asian series (mainly Chinese) into English, French, Swahili and Hausa, examples including The Beautiful Daughter-in-Law Era, The Ordinary World and Wildflower (left, from ABS CBN in the Philippines). Increasingly, it has also unveiled significant content investments and alliances from outside Asia. On the sports front, for example, it acquired exclusive live rights for UEFA Europa League in sub-Saharan Africa until 2021 (excluding South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland). It also signed deals with Discovery and Fox to air several channels via TV and OTT, including a new female lifestyle channel.

On the OTT front, SVOD services Fox+ and NG+ will join 70 channels already available on the StarTimes App, which the company says is able to reach 450 million mobile phone users via partnerships with 23 telecom operators. While it is too early to fathom StarTimes’ intention with regard to OTT, whether as an adjunct to pay TV or a stand-alone subscription service of some kind. Its current trajectory suggests it is well-placed to take advantage of OTT expansion, underlined by a deal in June between StarTimes and MTN that involves the latter offering bundles of entertainment, sports and news for US$0.50 (for two hours) or US$1 (for four hours) a day using the StarTimes app.

There is a sense that both StarTimes and MTN are feeling their way into the OTT market by trying out new content and pricing models on consumers. A possibility cited by Delta is that one company might emerge from the pack with a DAZN-style sports offering, though whether StarTimes, Kwese or MultiChoice (via its SuperSport operation) is best placed to win that battle is hard to call at this stage.

Brett Sappington notes that there is not necessarily an urgent incentive for players like StarTimes to commit to a standalone OTT service (as opposed to an integrated pay TV/OTT model). Already positioned as a low-cost pay TV provider, StarTimes’s status is perhaps more in line with the skinny bundle revolution taking place in the US.

This seems to chime with the view at Delta, where Modi and Archer say: “Unlike markets such as the US, where consumers are turning to on-demand service providers such as Amazon and Netflix and terminating pay TV services, cord cutting is still not a real threat in most African markets. Pay TV subscriptions continue to demonstrate robust growth which is expected to continue for the near future.”

This analysis would seem to be supported by Digital TV Research, which forecasts that the number of pay TV subscribers in sub-Saharan Africa will increase by 74% between 2017 and 2023 to reach 40.89 million. While Murray expects revenue growth to be slower (41%), that’s still a potential US$6.64 billion (by 2023) market for StarTimes to lean into.

iROKO: serving the Nigerian diaspora

While a lot of the heavy investment in Sub Saharan Africa has gone into South Africa, one of the first companies to identify Nigeria’s potential was iROKO, founded in 2010 by entrepreneurs Jason Njoku and Bastian Gotter. Backed by several tranches of investment from the likes of Goldman Sachs, Canal+ and Tiger Global, iROKO’s model has been built partly around acquiring Nollywood content and partly around low-cost local TV series and film production – increasingly delivered through the company’s in-house studio Rok Studios (movie titles in recent years include Birthmark and Desperate Housegirls, right).

While a lot of the heavy investment in Sub Saharan Africa has gone into South Africa, one of the first companies to identify Nigeria’s potential was iROKO, founded in 2010 by entrepreneurs Jason Njoku and Bastian Gotter. Backed by several tranches of investment from the likes of Goldman Sachs, Canal+ and Tiger Global, iROKO’s model has been built partly around acquiring Nollywood content and partly around low-cost local TV series and film production – increasingly delivered through the company’s in-house studio Rok Studios (movie titles in recent years include Birthmark and Desperate Housegirls, right).

While the company is pretty well-positioned compared to most, Parks Associates senior director of research Brett Sappington says its model to date has primarily been based around servicing the Nigerian diaspora, which is estimated at anywhere between 5-15 million.

IHS’s Constantinos Papavassilopoulos supports that observation: “Our estimates suggest around 60% of iROKO’s subscribers are outside Nigeria – markets like the US and UK – and 90% of its revenues. It charges international users an annual fee of US$50 but is only able to charge its customers around US$10 a year within the country.”

To put that in perspective, Digital TV Research estimates that iROKO currently has around 308,000 subscribers – which (using IHS’s percentage breakdown) would make it a US$10.5 million a year business. In 2016, Njoku told the Financial Times that iROKO was spending around US$7 million a year on content, which suggests it needs to see a step change in subscriptions to really starting getting traction. Digital TV Research is forecasting iROKO will have 1.5 million subs by 2023, though that will be offset by rising content costs as competitors target Nigeria. In its favour are first-mover advantage, and the fact that Njoku is realistic about the span of time it will take for OTT in this massive West African market to catch fire.

French and Portuguese-speaking Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa has around 250 million French-speakers across 23 countries. That may seem like a sizeable opportunity, although when you consider that 77 million are in the war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo it’s clear that OTT expansion is not always the most pressing priority. With instability in many of the region’s other populous French-speaking nations, the opportunity is actually relatively modest.

That said, the region’s leading pay TV player Canal+ is currently doing well. With 3.5-4 million subscribers, it is bullish about hitting five million by 2020, at a time when its domestic French business is suffering at the hands of platforms like Netflix. A key dimension for the company’s regional leadership has been investment in sports rights. But it is also investing in original content. An example of this is a tough contemporary series (10 x 52 mins) called Invisibles (left), set within Côte d’Ivoire’s gangland.

That said, the region’s leading pay TV player Canal+ is currently doing well. With 3.5-4 million subscribers, it is bullish about hitting five million by 2020, at a time when its domestic French business is suffering at the hands of platforms like Netflix. A key dimension for the company’s regional leadership has been investment in sports rights. But it is also investing in original content. An example of this is a tough contemporary series (10 x 52 mins) called Invisibles (left), set within Côte d’Ivoire’s gangland.

Although there is high penetration of mobile phones in the region (Canal+ expects 165 million to be in circulation by 2020), the same data charge issue faced in the English-speaking market has limited the potential of OTT/SVOD services. That said, Canal+ did launch a mobile SVOD service in partnership with iRoko in December 2015. As yet, there isn’t too much detail available on how that is going, though it’s worth noting additionally that a Nigerian music/lifestyle channel called iROKO Music was launched on Canal+’s pay TV service during mid-2017.

An illustration of how tough it is to make headway in this region as a standalone OTT service was the 2017 closure of Afrostream. Touted as the Netflix of French-speaking Africa, the service launched with 2,000 hours of local and international content and the ability to buy daily, weekly or monthly passes. Afrostream founder Tonjé Bakang put the failure of the service down to the high cost of content and slow service take up. Reports suggest Afrostream needed to reach 25,000 subscribers paying around US$6-7 a month to hit breakeven.

As for Lusophone Africa, there are between 15-30 million Portuguese-speaking people in Africa, mainly concentrated in Mozambique and Angola with not all using it as their first language. The key player in the region is ZapTV, a pay TV platform backed by Portuguese telco/TV operator NOS. The company has a catch up service called Restart TV and has been rolling out a fibre-based service, Zap Fibra, to complement satellite delivery.