Mixed fortunes: free-to-air and pay TV in the Middle East

Free TV, the mainstay of Middle Eastern broadcasting, has been badly hit by the impact of the region’s conflicts over the past year. But pay TV services and pan-Arab free-to-air is still growing. Stuart Thomson reports.

The Middle Eastern TV business has not been immune by any means from the conflicts that have plagued the region in recent years. But pay TV services have seen strong growth from a still relatively small base, while pan-Arab free-to-air broadcasters – notably MBC – appear better placed to weather the storm than other channel providers.

TV distribution in the Middle East remains overwhelmingly dominated by satellite – as can be seen from our map on the previous pages – and principally by free-to-air satellite TV, although there are some significant regional variations.

Pay TV is strong, for example, in the UAE, at least by comparison with other markets in the region, being the home to both OSN and Abu Dhabi Media as well as fixed-line operators Du and Etisalat. According to research group Ovum (owned by Digital TV Europe’s publisher Informa), pay digital satellite accounted for 30% of homes at the end of 2012, compared with 24% who took free-to-air digital satellite and 29% who took IPTV.

Over half of households in the UAE also take their TV from satellite, despite higher than average IPTV penetration for the region. According to Ovum, IPTV penetration is likely to increase over the next few years, but DTH will remain the leading distribution platform by a narrow margin. DTT is not expected to have a significant impact on the market, but OTT services are present, notably in the form of Dubai-based icflix, which launched in July last year. OSN also offers its Go by OSN as an OTT standalone offering across its footprint.

Qatar, home of Al Jazeera and, like the UAE, a member of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), is also exceptional in having very high pay TV penetration, at over 75%, according to Ovum, which expects pay TV revenues in the country to rise to US$51 million (€40 million) by 2017. In addition to DTH, Ooredoo, formerly Qatar Telecom, offers the Mozaic TV+ IPTV platform, which had 88,390 customers at the end of September 2013, giving IPTV a strong lead over DTH. A satellite dish ban was imposed 22 years ago but has not been enforced. OSN’s service is available via Ooredoo as well as via satellite. Bahrain also has robust pay TV penetration of over 50% at the end of 2012, according to Ovum, with Al Jazeera Sports/beIN Sports and OSN the major players. DTH is the dominant distribution platform with penetration of over 90%. As in Qatar, a satellite dish ban exists but has never been enforced.

Saudi Arabia, the largest GCC state, and the most culturally conservative, has lower pay TV penetration, with about a quarter of homes taking a pay TV service and about seven in 10 homes taking free-to-air DTH services. Saudi Telecom Company’s InVision IPTV service had about 160,000 subscribers by September 2013, according to Ovum, offering a range of packages over DSL and fibre networks via a hybrid IPTV/DTH platform to enable users to access free-to-air satellite channels.

DTT is stronger in Saudi Arabia than elsewhere in the region, with the country rolling out a service as long ago as 2006. Saudi Arabia-based technology provider Selevision recently teamed up with satellite operator Arabsat to launch what the pair say will be the first HbbTV-based service in the Middle East and North Africa region.

YouTube is extremely popular among the younger demographic in the country, helping to boost mobile OTT viewing in particular.

Elsewhere in the region, free-to-air TV is overwhelmingly dominant. Even Oman, another GCC state, has pay TV penetration of only about 7%, with the overwhelming majority of people accessing free-to-air channels only.

In the largest Arabic market, Egypt, according to Ovum, only about 6% paid for TV services at the end of 2012 – which nevertheless represented 1.1 million homes. The country had 21.2 million TV homes at the end of 2012, with about three in six using DTH as their primary means of receiving channels, with the remainder primarily analogue terrestrial services. The majority of services were free-to-air.

Major broadcasters include state provider ERTU, with both national and regional services, Nile Television Network, with a variety of thematic channels covering most genres

Piracy remains a major problem in the region. Pressure put by rightsholders on satellite operator Nilesat has resulted in the removal of channels that carry pirated content – for example Panorama Comedy and Panorama Action in July 2013.

Major broadcasters that have launched services in the region include MBC, which launched MBC MASR, its dedicated Egyptian channel, in 2012, while Saudi Arabia-based Rotana Group launched its own channel, the Masriya Channel, offering a mix of general entertainment targeted at an Egyptian audience, in 2011.

News broadcasters have also entered the fray, with Al Arabiya launching a local channel, Al Hadath, in 2012. Al Jazeera’s service, Al Jazeera Mubasher, has run into problems in the country since the fall of former president Mohammed Morsi, with an administrative court ordering it to be taken off air in September, despite the fact that the channel is actually broadcast via Eutelsat and is therefore outside Egypt’s power to remove.

OTT services remain in their infancy. OSN Play and icflix are both present in Egypt.

Ovum predicted in its last Egypt update that there will be 2.2 million DTT homes in 2017, with analogue holding the major share as far as terrestrial reception is concerned.

Elsewhere in the region, Jordan has low pay TV penetration, with Ovum expecting that pay TV will reach only 6% of households by 2017. Free digital satellite accounted for over 80% of homes at the end of 2012.

In war-torn Syria, meanwhile, pay TV is even more of a minority pursuit, with Ovum estimating that fewer than 1% of households took a pay TV service at the end of 2012. Free-to-air satellite accounts for 85% of household reception.

Advertising market

The prevalence of conflict in key parts of the region over the last few years – first with the wave of revolutions of 2011 and latterly with post-revolutionary turmoil in Egypt, the Syrian civil war and continued and worsening conflict in Iraq, as well as strife in Gaza and Yemen – has had a disastrous impact on the free-to-air TV market. While pay TV businesses in markets far from conflict have in fact remained relatively robust, the advertising business has suffered multiple crises.

According to Sami Raffoul, general manager of the Dubai office of the Pan-Arab Research Centre (PARC), the multiple crises suffered by the region over the last few years have not only adversely impacted the advertising business in the territories immediately subject to conflict but has had a knock-on effect across the entire region.

The Syrian crisis – and its spillover into neighbouring countries, notably Iraq – in particular severely affected the advertising business. The burden of looking after refugees has impacted neighbouring countries such as Jordan and Lebanon, sucking resources out of the wider economy. In areas far from the war, workers of Syrian origin who previously spent money in the local economy have instead sent what cash they can home to help their families survive. Images of conflict on the TV news have also acted as a brake on advertisers who are reluctant to be seen as insensitive.

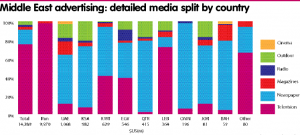

According to Raffoul, pan-Arab media, meaning those TV channels that are broadcast across the Arab region to a wide audience, have continued to grow, but at a much lower rate than was previously the case. According to figures compiled by PARC, pan-Arab media turned in revenues of US$9.97 billion in 2014, up 19% year-on-year. However, it is not clear how much the advertising rate card of channels reflects the actual purchase price of advertising inventory, so figures have to be taken cautiously. This is particularly the case as pan-Arab media includes a number of Egyptian channels that initially used pan-Arab distribution primarily as a way to target their own domestic audience, unhindered by domestic restrictions, but found a ready audience in other parts of the Arab world, including Saudi Arabia and the Gulf, where large numbers of Egyptian migrant workers are present.

At a national level, only Egypt and Lebanon recorded growth overall, with Egypt growing 3% to US$1.068 billion and Lebanon posting growth of 9% to US$364 million.

According to Raffoul, Egypt has performed well only relative to the prior year, characterised by the political crises leading up to the fall of the Morsi government, with the market still short of the level of 2012, let alone the pre-revolutionary era. In the case of Lebanon, the real rate of growth is hard to estimate with accuracy, but Raffoul believes the level of advertising activity may have been boosted by the arrival of an effective independent audience measurement system provided by GfK.

Other markets have suffered badly. PARC estimates that the Saudi market fell by 9% last year, while Oman fell by a staggering 21%.

Dubai-based pan-Arabic broadcaster MBC is, says Raffoul, “probably the only really robust player in the region”, thanks to its abilities to invest in quality programming that can be broadcast across the region while also investing in a local presence where it makes sense – notably with its MBC MASR channel for Egypt. Raffoul also praised MBC’s decision to invest in local sports by, for example, taking the rights to the Saudi football league. While other broadcasters have invested heavily in international sports rights, he says that often such rights have not been successfully exploited, failing to generate sufficient revenues to justify the investment.

Raffoul says that digital media continues to grow across the region, appealing strongly to a more youthful demographic.

He estimates from anecdotal sources that digital currently accounts for “five to seven per cent of ad budgets”. Digital includes the web, mobile and social media. Both international players including Google and local news and other media are benefiting from increased web traffic. However, he points out, local and regional news content, though popular, does not necessarily lend itself to advertising, particularly as much of the news coming out of the region relates to conflict. YouTube is increasingly popular, with countries including Saudi Arabia leading the way, as noted above.

One advantage of digital media is that usage can be measured highly accurately. For broadcast channels, audience measurement remains challenging. Egypt’s plans to develop a TV metering system were interrupted by the revolution. The UAE has implemented a system that has attracted both positive and negative coverage, with some broadcaster challenging its statistics. It has recently been audited, with the results of that audit still to be published. Saudi Arabia has, according to Raffoul, watched the UAE experiment closely and is now implementing its own audience metering system, supplied and managed by GfK. The first data is promised during the first half of next year.

Pay TV growth

GfK has already implemented a metering system for Lebanon, with data available since the early part of this year, and Raffoul says that this in part explained how that country defied the overall trend across the region for advertising revenues to fall over 2014, despite its proximity to the Syrian conflict.

Pay TV has made significant progress in recent years across the Middle East, with OSN in particular growing its base significantly recently. The other major pay TV players are all Gulf-based, with Qatar’s Al Jazeera/beIN Sports and Saudi Arabia-based Al Majd providing competition. Another major player is UAE-based Abu Dhabi Media Group, which recently took the decision to supply its channels to OSN rather than continue to invest in its own proprietary platform to reach subscribers.

According to Dennis Lehtinen, head of pay TV operations at Abu Dhabi Media, pay TV is mainly growing in the GCC countries, and the main drivers, as elsewhere in the world, are exclusive sports, including the main European football leagues, movies and TV series – both from western countries and from the Arabic world and Turkey. He says that free-to-air broadcasters have secured pay TV window rights and OTT rights to diversify their revenue streams, and suggests that the market could be opened out and pay TV penetration improved if low-cost operators such as My-HD, a Gulf-based operator that launched last year, are successful. At the other end of the spectrum, consolidation of pay TV groups ART, ADM and Filipino channel provider Pehla TV has enabled OSN to offer a unified platform with a range of content available via a single receiver. Lehtinen also points out that IPTV in the UAE, where dishes are banned in many areas, can also facilitate pay TV expansion. The development of fixed-line networks could also facilitate growth in a number of other Gulf markets.

Adu Dhabi Media itself, says Lehtinen, will focus primarily on developing its sports channels, “both with international and local content, production of sport shows, developing studios around sports events and so on”. He points out that local football leagues could help drive pay TV take-up. “The encryption of the Arabian Gulf League has been a big success with a high subscriber growth in the UAE. The concept of encrypting local football leagues could be a future driver for pay TV in the region, similar to many developed pay TV markets,” he says. Lehtinen points out that while sports is a key driver for pay TV, the economics of delivering international league football are problematic. “Premium sport is the main driver for pay TV growth. However the cost for sports rights compared to their consumer affordability in the region, where only an estimated 10 million households in MENA can actually afford premium pay TV, makes it hard to find a business model to make pay TV work commercially, at least for the short term,” he says.

Lehtinen suggests that local football rights are an underused resource – something also recognised by OSN, which has commercialised rights to the popular Saudi league. He says that Abu Dhabi Media could look to invest further in this area. “Abu Dhabi Media’s long term strategy for sports rights is under development, and during the coming months it will be more clear what offering will be available on Abu Dhabi Sports channels,” he says. “As mentioned before, local football – except for the Saudi league – could be something ADM invests in based on the success of the Arabian Gulf League. However nothing is decided yet.”

Lehtinen says Abu Dhabi Media is also planning to launch its own first-run drama channel, AD Drama+, in January, introducing a 60-90 day window for pay TV before the content is shown on free-to-air.

Piracy threat

Piracy has long been a major threat across the region, both to pay TV and free-to-air channels. While the former have been subject to control word sharing attacks and – increasingly – illegal streaming of content, free channels have also suffered from other broadcasters illegally picking up their content and rebroadcasting it.

For Lehtinen, speaking about the pay TV market, piracy remains the key hurdle preventing growth. “Piracy is the main obstacle for pay TV and other IP owners in the region. The main threat is live streamed sport content and the download of premium general entertainment through the internet. As broadband penetration increases the piracy threat increases,” he says. “When it comes to live sport, encryption providers, such as Irdeto, continue work to discover and block URLs providing free access to premium services. However the main strategy is to work closely with governments to legally battle piracy. One challenge in many countries in the region is the low priority for IP protection due to other domestic challenges.”

For Lehtinen, piracy is likely to remain a problem, and the best defence of pay TV operators will be to deliver a compelling user experience that pirate services can’t match. “In the short to medium term piracy will be the main challenge for the growth of pay TV in the region and with this in mind the pay TV operators need to focus on the quality on the screen, developing customer experience such as multi-screen offerings, HD broadcasting and excellent customer service,” he says.

For the free-to-air market, while illegal rebroadcasting remains a problem, PARC’s Raffoul suggests that the majority of TV players now understand that there are limits to what they can get away with. “Respect for rights has been heightened by a few cases against those who have infringed,” he says.

However, it remains true that the more powerful broadcasters protect their own rights by taking action against infringers independently. Not every legitimate channel provider can afford to monitor what is being broadcast on so many channels across such a large region. The burden is ultimately on broadcasters to prove that their content is being redistributed illegally. Rightsholders are also challenged by out-of-region broadcasters with legitimate rights in their domestic market targeting expatriates, for example in the Gulf, with content to which they don’t hold rights for in the region.

In some respects, the prevalence of piracy is a testament to the robust demand for services that exists across the Middle East, despite the problems the region faces. While the advertising market faces challenges, this has yet to result is a wholesale cull of channels.

Despite the problems associated with the region’s conflicts, pan-Arab TV – both free and pay TV – is still in growth, and the region’s main players are still looking for new projects and content to build their offerings.